Meaning and Socialization in the Information Age

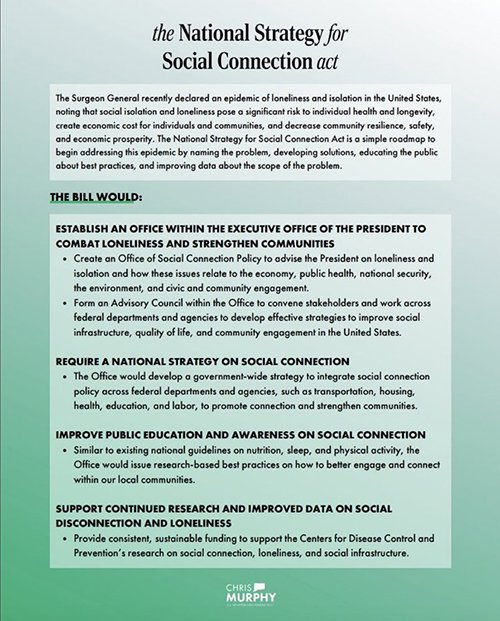

Reading Time: 7 minutes, 39 secondsI noticed today that Connecticut Senator Chris Murphy introduced new legislation: "The National Strategy for Social Connection Act". The Act purports to solve the issue of "loneliness and isolation". Let's leave aside whether we should run screaming in terror at the very idea of the government imposing "nutrition, sleep, and physical activity" guidelines on the general population. Let's also leave aside whether such a proposed strategy would actually solve the problem it purports to solve. The problem does exist, and it's getting worse. It's been getting worse for a while now, actually.

Perhaps, unsurprisingly, I think that it's directly related to the changes that began with the start of the Book Age, and have been made worse by the start of the Information Age. The Book Age failed our culture in a major way, and the Information Age is failing us in a different, but related way.

Perhaps, unsurprisingly, I think that it's directly related to the changes that began with the start of the Book Age, and have been made worse by the start of the Information Age. The Book Age failed our culture in a major way, and the Information Age is failing us in a different, but related way.

One of the things the Church Age provided was eternal verities. It was an age of unquestioned axioms, one of the most important of which was that life was anchored in religion. The religion of the Church Age bought to bear a philosophy that provided answers to deep questions about the nature and meaning of existence. It imposed social obligations—unevenly of course—on everyone. Everyone knew their place in the social order, and why they were in it. It provided a hope for the future, in the next life, if not in this one, of eternal rewards for virtue and obedience. And, on a more basic, human level, the Church offered a central social place for routinized meeting, networking, and socialization on a recurring, ongoing basis.

That isn't to say that life for the average peasant during the Church Age was pleasant or easy. Life was, as Hobbes wrote, nasty, brutish and short in most cases. Daily life was often filled with back-breaking physical labor. Opportunities for social or economic improvement were, from our perspective, unimaginably limited. But, in compensation, what the philosophy of the Church provided was a holistic viewpoint about life that provided both comfort and hope.

As long, of course, as you didn't question the premises of that philosophy too thoroughly. Which was exactly the sort of questioning that the Book Age brought. New ideas and new modes of thinking prompted questions about how much of the Church's philosophy was grounded in good faith, and how much in supporting a particular arrangement of political power. Certainly the cynical and hypocritical activities of the Church's leaders, which prompted the Protestant Reformation, weighed heavily in such questions. With the rise of the scientific method, questions also arose about how much of Church Age philosophy was grounded in facts or rationality.

Looking back from today, the 19th century often seems to us a time of strong religious faith. But, even then, the loss of faith and a crisis of meaning was coming to a head. In the first half of the 19th century, Arthur Schopenhauer concluded that life was an unending parade of misery that, at best, we could endure until freed by death. Basically, "Life sucks, and then you die."

Influenced by the work of Schopenhauer, it was Friedrich Nietszche, however, who penned this cry from the heart in 1882:

Influenced by the work of Schopenhauer, it was Friedrich Nietszche, however, who penned this cry from the heart in 1882:

God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? What was holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet owned has bled to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood off us? What water is there for us to clean ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we have to invent? Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?

This was not, at its core, a statement of triumph or joy. It was a cry of mourning. The rise of materialism and secularism in the 18th and 19th centuries had effectively, as a matter of both social and political governance, killed off the religiosity of the Church Age, even if most common people hadn't yet realized it. And in 1882, this loss of meaning was only just beginning, as was the philosophical crisis that this loss of meaning imposed.

As naturalistic explanations for the nature of the world and cosmos found greater and greater scope, the explanatory power of Church Age religious philosophy was crammed into a tighter and tighter corner. Many of the Church Age explanations for the nature of the cosmos seemed incorrect at best, and ridiculous at worst. The result, as the disastrous 20th century ground on, was a growing loss of faith in traditional institutions and, eventually, a growing cynicism about Western culture in general.

The Book Age took away the meaning provided by the central Pillar of the Church Age, and replaced it with...nothing. And that brings us to our problem.

Life without meaning, and even worse, life without hope, seems more bleak than most people wish to contemplate. There is, in nearly everyone, a deep sense that the pain we endure and the joys we celebrate must mean something. A sense that life cannot be a mere happenstance, cannot be a transient flicker in the darkness, filled by eternal nothingness. In the Church Age, nearly everyone, from peasant to king, had a fulfilling answer to these questions. The Book Age stripped that philosophical certainty from us, but offered us no replacement for it.

Science could explain the origins of the universe, and the evolution of life, but, when asked about whether there was a soul and life after death, or whether our existence was evidence of anything transcendental, just noped right out. "Sorry, we can only address factual questions that can be answered by accessible physical evidence. Also, we're a big no on moral and ethical questions, too. Science doesn't do that. Sorry." Atheism doesn't offer answers to any questions about meaning, either, other than negatives. "Nope. No soul. No life after death. You're born, do whatever you can, then you're gone forever. This is it. Deal with it."

Now, individually, each person has their own need for meaning, or answers to transcendent questions of existence. Personally, I'm not bothered much by deep questions about meaning. But I'm not foolish enough to pretend that others aren't or argue that they shouldn't be. In aggregate, a culture, to remain vital, vibrant, and strong, needs to have some philosophy that provides meaning, and to pursue that meaning through goals and actions. A culture needs purpose, even if some portion of its members, individually, do not. A culture without meaning turns in on itself, and cannibalizes itself.

If the culture cannot provide the meaning that people crave, they'll seek out their own meaning, often in destructive ways. Most of the cultural issues that divide us are, in the most fundamental sense, a result of people reaching out for meaning. People who destroy paintings in museums or glue themselves to streets to protest the use of oil are not simply well-meaning environmentalists. The struggle against oil has become the central meaning of their lives. Increasingly, politics is becoming a secular religion that provides daily meaning to life, along with giving us a set of ideological heretics to revile. One can, on the one hand, revile cisgendered white males, or, on the other hand, the commie Never-Trumpers. These are not healthy substitutes for meaning. They are, however, the only substitutes for it in a culture that has no other meaning to offer.

The arrival of the Information Age has only exacerbated this problem. The trend towards individual atomization in society was started by the Book Age. The trend towards urbanization in the 20th century is one example. People left the traditional ways of the countryside, where they lived in smaller communities where they knew, and were known by, everyone in the community. They found themselves living in cities full of strangers. Membership in churches or social clubs declined. People were increasingly isolated. In 2000, Harvard professor Robert Putnam wrote Bowling Alone, which used a vast amount of data to show that Americans "have become increasingly disconnected from family, friends, neighbors, and our democratic structures".

It's becoming increasingly difficult for younger people to engage in relationships with the opposite sex, as the traditional avenues for meeting and getting to know potential mates, such as Church, social clubs, and the like are increasingly unavailable. And in forums where one might meet and get to know potential mates, such as work, are increasingly bound by rules against such personal interactions, to avoid sexual harassment or other issues.

The Information Age makes this problem worse, as technology increasingly eliminates the need for person-to-person contact. From remote work, to instant access to porn, to online relationships in chat groups, to social media, the Information Age makes it increasingly possible to exist in an environment that provides access only to simulacrums of social contact, while providing no human contact at all.

The crisis of meaning is thus joined by its twin crisis of loneliness. And, just as the Book Age provided no replacement to alleviate the crisis of meaning, the Information Age offers no replacement to alleviate the crisis of loneliness.

With all respect to Senator Murphy, I cannot say I have any confidence that the government can solve the crisis of loneliness. In my lifetime, I've watched the government's hapless attempts to solve the crises of poverty, homelessness, Vietnam, Islamic fundamentalism, and immigration. Those efforts inform my estimation of the government's success at doing anything but spending money with little to show for it in return.

Moreover, and more importantly, cultural crises—and make no mistake, we are in crisis—are not solved by government. Governments are the product of cultural decisions. They reflect culture, they do not, except perhaps in the most pernicious of totalitarian states, create or control culture. And I would not wish to live in a state that tries to control the culture.

We've come to believe more and more that our problems are the result of some deficiency in our political system. "If only," we say to ourselves, "my side could win more votes. If only we could get a few more seats on the Supreme Court." Then, we think, many of our problems could be solved. But that's not the answer at all. The answer can only come from the culture itself, and any other method we try to use to solve these cultural problems will fail.

The great and daunting task before us is to find some way to revitalize our culture in a way that provides meaning and a sense of belonging. We must find a path forward that engages as many people as possible with a hopeful vision of the future. It probably won't be one, as our ancestors had, that promises eternal life in heaven. For better or for worse, that shared vision now lies dead in the remote past for many people—indeed, for most people in the West. But we must find a cultural philosophy that provides a deeper sense of meaning than mere existence, and a vision of something greater than living for ourselves. Moreover, it must be a philosophy that has universal appeal, just as the religious philosophy of the Church resonated with both peasants and emperors.

Creating this new cultural philosophy can't simply be a hope or a dream. It is a necessity. Our culture is dying. If we cannot fix it, then our culture is finished.